Quantum Chromodynamics in High-Energy Colliders

One key ingredient to the Standard Model is quantum chromodynamics (QCD), describing the interaction of particles via the strong force. Its understanding is of profound importance as, e.g., the strong interaction is predominantly responsible for the matter from which humans are formed and, in general, for most of the mass of the visible universe. Moreover, precise knowledge of hadron structure is often essential in searches for New Physics beyond the Standard Model. QCD explains the interaction of point-like quarks via the exchange of gluons, the gauge bosons of QCD. Numerous experiments have verified many aspects of perturbative QCD (pQCD) in processes involving large momentum transfers.

However, even after a roughly 50-years success story of QCD, it is still an outstanding problem how QCD works in detail on long-distance scales and/or in real-time evolution. The dynamics of quarks and gluons inside hadrons and how they shape the properties of the latter, e.g., how the inner constituents of the proton interplay to form what we know as a proton, remain to be a challenge. A prominent example is the proton’s mass or angular momentum, e.g., the spin of the proton and how it comes about from the angular momenta of the proton’s constituents. Similarly, how hadrons are formed from quarks and gluons ejected in a high energy process at the LHC or in the electron-positron annihilation process remains an equally intriguing as challenging problem.

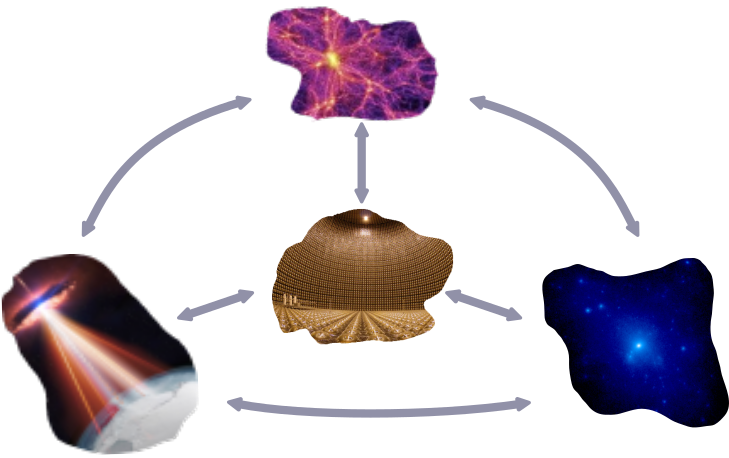

Moreover, our understanding of QCD is primarily based on scattering experiments, whereas the dynamics of QCD matter in the cores of compact stars and during the early evolution of the Universe remain poorly understood due to the limited theoretical and experimental tools available for such problems. Such QCD matter under extreme conditions can be studied in heavy-ion collisions (HIC), which provide a window into the real-time evolution of matter at extremely large temperatures and densities—conditions similar to those encountered in cosmological and astrophysical systems. However, the lack of adequate theoretical tools still prevents the community from making decisive progress in these directions.

Our group develops new tools to extract information from experiments at e.g. CERN, JLab, BNL or KEK, and future planned ones like the fixed-target experiments at CERN or the future Electron-Ion Collider in the United States.